The UCR-based Alternative Earth’s Team has received a five-year funding award from the Interdisciplinary Consortium for Astrobiology Research (ICAR). VPL…

Earth’s carbon cycle maintains a stable climate and biosphere on geological timescales. Feedbacks regulate the size of the surface carbon reservoir, and on million‐year timescales the carbon cycle must be in steady state. A major question about the early Earth is whether carbon was cycled through the surface reservoir more quickly or slowly than it is today. The answer to this question holds important implications for Earth’s climate state, the size of the biosphere through time, and the expression of atmospheric biosignatures on Earth‐like planets. Here, we examine total carbon inputs and outputs from the Earth’s surface over time. We find stark disagreement between the canonical histories of carbon outgassing and carbon burial, with the former implying higher rates of throughput on the early Earth and the latter suggesting sluggish carbon cycling. We consider solutions to this apparent paradox and conclude that the most likely resolution is that high organic burial efficiency in the Precambrian enabled substantial carbon burial despite limited biological productivity. We then consider this model in terms of Archean redox balance and find that in order to maintain atmospheric anoxia prior to the Great Oxidation Event, high burial efficiency likely needed to be accompanied by greater outgassing of reductants. Similar mechanisms likely govern carbon burial and redox balance on terrestrial exoplanets, suggesting that outgassing rates and the redox state of volcanic gases likely play a critical role in setting the tempo of planetary oxygenation.

VPL researcher Dr. Sarah Keller has been named a 2021 Fellow of the Biophysical Society for “pioneering, fundamental experimental contributions…

Here we use an array of major and trace element data to constrain the redox conditions in the water column and extent of basinal restriction during deposition of the ZF. We also present new selenium (Se) abundance and isotopic data to provide firmer constraints on fluctuations across high redox potentials, which might be critical for phosphogenesis. We find that Se isotope ratios shift over a range of ~3‰ in the ZF, with the earliest stratigraphically-resolved negative Se isotope excursion in the geologic record, implying at least temporarily suboxic waters in the basin. Furthermore, we find that redox-sensitive element (RSE) enrichments coincide with episodes of P enrichment, thereby implicating a common set of environmental controls on these processes. Together, our dataset implies deposition under a predominantly anoxic water column with periodic fluctuations to more oxidizing conditions because of connections to a large oxic reservoir containing Se oxyanions (and other RSE’s, as well as sulfate) in the open ocean

VPL Team members Roy Black, Sarah Keller and other collaborators in the Keller Lab in the Chemistry Department at the…

Deputy PI and Task B Co-Lead, Giada Arney, and one of the VPL team’s resident Venus experts, was recently honored…

Giada Arney works at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and as part of the VPL team is the Project Deputy…

Are we alone in the universe? How did life arise on our planet? How do we search for life beyond…

The origin of life is perhaps the most perplexing unanswered question in science. The main reason for this perplexity is the overlap of four critical components to lifes origin: when and where life emerged, how it formed, and what the earliest life forms looked like. Each of these components has their own set of questions that cross multiple disciplines. For example, insights into the question of when and where life began are predicated on the early Archaean rock record, which is limited due to metamorphism and erosion. With time, continued study of the rock record will reveal more about the…

We present a study of the photochemistry of abiotic habitable planets with anoxic CO2–N2 atmospheres. Such worlds are representative of early Earth, Mars, and Venus and analogous exoplanets. Photodissociation of H2O controls the atmospheric photochemistry of these worlds through production of reactive OH, which dominates the removal of atmospheric trace gases.

VPL scientist Dr. Eddie Schwieterman (UCR) was recently featured on the Ask an Astrobiologist program! You can watch a recording…

We have only one example of an inhabited world, namely Earth, with its thin veneer of water, the solvent essential to known life. Is a terrestrial planet like Earth that lies in the habitable zone and has the ingredients of habitability a common outcome of planet formation or an oddity that relied on a unique set of stochastic processes during the growth and subsequent evolution of our solar system?

Ultimately, water originates in space, likely formed on dust grain surfaces via reactions with atoms inside cold molecular clouds (Tielens and Hagen, 1982; Jing et al., 2011). Grain surface water ice…

Are we alone in the universe? How did life arise on our planet? How do we search for life beyond Earth? These profound questions excite and intrigue broad cross sections of science and society. Answering these questions is the province of the emerging, strongly interdisciplinary field of astrobiology. Life is inextricably tied to the formation, chemistry, and evolution of its host world, and multidisciplinary studies of solar system worlds can provide key insights into processes that govern planetary habitability, informing the search for life in our solar system and beyond. Planetary Astrobiology brings together current knowledge across astronomy, biology, geology, physics, chemistry, and related fields, and considers the synergies between studies of solar systems and exoplanets to identify the path needed to advance the exploration of these profound questions.

Planetary Astrobiology represents the combined efforts of more than seventy-five international experts consolidated into twenty chapters and provides an accessible, interdisciplinary gateway for new students and seasoned researchers who wish to learn more about this expanding field. Readers are brought to the frontiers of knowledge in astrobiology via results from the exploration of our own solar system and exoplanetary systems. The overarching goal of Planetary Astrobiology is to enhance and broaden the development of an interdisciplinary approach across the astrobiology, planetary science, and exoplanet communities, enabling a new era of comparative planetology that encompasses conditions and processes for the emergence, evolution, and detection of life.

Full Citation: Meadows V. S., Arney G. N., Des Marais D. J., and Schmidt B. E. (2020). Preface. In Planetary…

The development of astrobiology, the study of life in the universe, is intimately tied to the development of spaceflight in the mid to late twentieth century, which enabled the discovery and exploration of non-Earth environments that might harbor life. In 1976, the Viking missions to Mars supported a core goal to search for signs of life beyond Earth (Klein et al., 1972). However, the Viking life detection experiments provided inconclusive evidence of organics and life (e.g., Klein, 1979; Biemann, 1979; Quinn et al., 2013), a result that put a damper on both Mars exploration and exobiology (as astrobiology was known…

Owen Lehmer (University of Washington, Advisor: David Catling) successfully defended his dissertation for his Dual-Title PhD in Earth and Space…

Strong seismic waves from the July 2019 Ridgecrest, California, earthquakes displaced rocks in proximity to the M 7.1 mainshock fault trace at several locations. In this report, we document large boulders that were displaced at the Wagon Wheel Staging Area (WWSA), approximately 4.5 km southeast of the southern terminus of the large M 6.4 foreshock rupture (hereafter “the large foreshock”) and 9 km southwest of the nearest approach of the M 7.1 mainshock surface rupture

Chemical disequilibrium in exoplanetary atmospheres (detectable with remote spectroscopy) can indicate life. The modern Earth’s atmosphere–ocean system has a much larger chemical disequilibrium than other solar system planets with atmospheres because of oxygenic photosynthesis. However, no analysis exists comparing disequilibrium on lifeless, prebiotic planets to disequilibrium on worlds with primitive chemotrophic biospheres that live off chemicals and not light. Here, we use a photochemical–microbial ecosystem model to calculate the atmosphere–ocean disequilibria of Earth with no life and with a chemotrophic biosphere.

The balance between carbon outgassing and carbon burial controls Earth’s climate on geological timescales. Carbon removal in carbonates consumes both atmospheric carbon and ocean carbonate alkalinity sourced from silicate weathering on the land or seafloor. Reverse weathering (RW) refers to clay-forming reactions that consume alkalinity but not carbon. If the cations (of alkalinity) end up in clay minerals rather than in the carbonates, carbon remains as atmospheric , warming the climate. Higher silicate weathering fluxes and warmer temperatures are then required to balance the carbon cycle. It has been proposed that high dissolved silica concentrations resulting from the absence of ecologically significant biogenic silica precipitation in the Precambrian drove larger RW fluxes than today, affecting the climate. Here, we present the first fully coupled carbon-silica cycle model for post-Hadean Earth history that models climate evolution self-consistently (available as open source code). RW fluxes and biogenic silica deposition fluxes are represented using a sediment diagenesis model that can reproduce modern conditions. We show that a broad range of climate evolutions are possible but most plausible scenarios produce Proterozoic warming (+5 K relative to without RW), which could help explain the sustained warmth of the Proterozoic despite lower insolation. RW in the Archean is potentially more muted due to a lower land fraction and sedimentation rate. Key model uncertainties are the modern reverse weathering flux, the rate coefficient for RW reactions, and the solubility of authigenic clays. Consequently, within the large uncertainties, other self-consistent scenarios where Proterozoic RW was unimportant cannot be excluded. Progress requires better constraints on parameters governing RW reaction rates including explicit consideration of cation-limitations to Precambrian RW, and perhaps new inferences from Si or Li isotopes systems.

We attempted to use vesicle sizes in lavas erupted near sea-level from the ~2.9 Ga Pongola Supergroup from Mahlangatsha and Mooihoek, eSwatini (formerly Swaziland) and the White Mfolozi River gorge of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa to provide further Archean paleobarometric data. However, reliable results were unobtainable due to small and scarce amygdales, irregular vesicle morphologies and metamorphic mineralogical homogenization preventing the use of X-ray Computed Tomography for accurate vesicle size determination. Researchers attempting paleobarometric analysis using lava vesicle sizes should henceforth avoid these areas of the Pongola Supergroup and instead look at other subaerially emplaced lava flows. With this being only the second time this method has been used on Precambrian rocks, we provide a list of guidelines informed by this study to aid future attempts at vesicular paleobarometry.

The atmosphere of the Archean eon—one-third of Earth’s history—is important for understanding the evolution of our planet and Earth-like exoplanets. New geological proxies combined with models constrain atmospheric composition. They imply surface O2 levels <10−6 times present, N2 levels that were similar to today or possibly a few times lower, and CO2 and CH4 levels ranging ~10 to 2500 and 102 to 104 times modern amounts, respectively. The greenhouse gas concentrations were sufficient to offset a fainter Sun. Climate moderation by the carbon cycle suggests average surface temperatures between 0° and 40°C, consistent with occasional glaciations. Isotopic mass fractionation of atmospheric xenon through the Archean until atmospheric oxygenation is best explained by drag of xenon ions by hydrogen escaping rapidly into space. These data imply that substantial loss of hydrogen oxidized the Earth. Despite these advances, detailed understanding of the coevolving solid Earth, biosphere, and atmosphere remains elusive, however.

University of Washington graduate student and VPL collaborator Owen Lehmer, was the lead author of a new paper recently published…

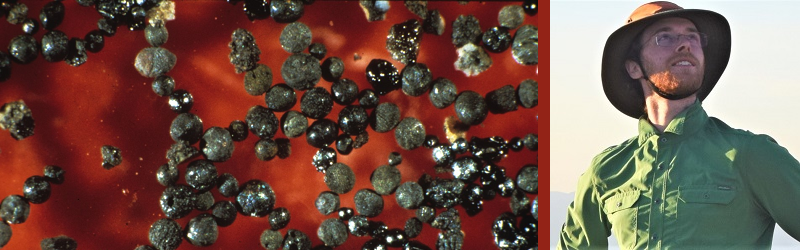

Earths atmospheric composition during the Archean eon of 4 to 2.5 billion years ago has few constraints. However, the geochemistry of recently discovered iron-rich micrometeorites from 2.7 billionyearold limestones could serve as a proxy for ancient gas concentrations. When micrometeorites entered the atmosphere, they melted and preserved a record of atmospheric interaction. We model the motion, evaporation, and kinetic oxidation by CO2 of micrometeorites entering a CO2-rich atmosphere. We consider a CO2-rich rather than an O2-rich atmosphere, as considered previously, because this better represents likely atmospheric conditions in the anoxic Archean. Our model reproduces the observed oxidation state of micrometeorites at 2.7 Ga for an estimated atmospheric CO2 concentration of >70% by volume. Even if the early atmosphere was thinner than today, the elevated CO2 level indicated by our model result would help resolve how the Late Archean Earth remained warm when the young Sun was ~20% fainter.

We make the case that marine processes are an important component of the canonical silicate weathering feedback, and have played a much more important role in p CO2 regulation than traditionally imagined. Notably, geochemical evidence indicate that the weathering of marine sediments and off‐axis basalt alteration act as major carbon sinks. However, this sink was potentially dampened during Earth’s early history when oceans had higher levels of dissolved silicon (Si), iron (Fe), and magnesium (Mg), and instead likely fostered more extensive carbon recycling within the ocean‐atmosphere system via reverse weathering—that in turn acted to elevate ocean‐atmosphere CO2 levels.

Phosphate is central to the origin of life because it is a key component of nucleotides in genetic molecules, phospholipid cell membranes, and energy transfer molecules such as adenosine triphosphate. To incorporate phosphate into biomolecules, prebiotic experiments commonly use molar phosphate concentrations to overcome phosphates poor reactivity with organics in water. However, phosphate is generally limited to micromolar levels in the environment because it precipitates with calcium as low-solubility apatite minerals. This disparity between laboratory conditions and environmental constraints is an enigma known as the phosphate problem. Here we show that carbonate-rich lakes are a marked exception to phosphate-poor natural waters. In principle, modern carbonate-rich lakes could accumulate up to ?0.1 molal phosphate under steady-state conditions of evaporation and stream inflow because calcium is sequestered into carbonate minerals. This prevents the loss of dissolved phosphate to apatite precipitation. Even higher phosphate concentrations (>1 molal) can form during evaporation in the absence of inflows. On the prebiotic Earth, carbonate-rich lakes were likely abundant and phosphate-rich relative to the present day because of the lack of microbial phosphate sinks and enhanced chemical weathering of phosphate minerals under relatively CO2-rich atmospheres. Furthermore, the prevailing CO2 conditions would have buffered phosphate-rich brines to moderate pH (pH 6.5 to 9). The accumulation of phosphate and other prebiotic reagents at concentration and pH levels relevant to experimental prebiotic syntheses of key biomolecules is a compelling reason to consider carbonate-rich lakes as plausible settings for the origin of life.