Title: Postdoctoral Research Associate in Planetary Geochemistry Applications are invited for a postdoctoral scholar to work on planetary geochemistry using…

VPL graduate student Nick Wogan (University of Washington), researcher and former student Dr. Josh Krissansen-Totton (University of California, Santa Cruz)…

Earth’s carbon cycle maintains a stable climate and biosphere on geological timescales. Feedbacks regulate the size of the surface carbon reservoir, and on million‐year timescales the carbon cycle must be in steady state. A major question about the early Earth is whether carbon was cycled through the surface reservoir more quickly or slowly than it is today. The answer to this question holds important implications for Earth’s climate state, the size of the biosphere through time, and the expression of atmospheric biosignatures on Earth‐like planets. Here, we examine total carbon inputs and outputs from the Earth’s surface over time. We find stark disagreement between the canonical histories of carbon outgassing and carbon burial, with the former implying higher rates of throughput on the early Earth and the latter suggesting sluggish carbon cycling. We consider solutions to this apparent paradox and conclude that the most likely resolution is that high organic burial efficiency in the Precambrian enabled substantial carbon burial despite limited biological productivity. We then consider this model in terms of Archean redox balance and find that in order to maintain atmospheric anoxia prior to the Great Oxidation Event, high burial efficiency likely needed to be accompanied by greater outgassing of reductants. Similar mechanisms likely govern carbon burial and redox balance on terrestrial exoplanets, suggesting that outgassing rates and the redox state of volcanic gases likely play a critical role in setting the tempo of planetary oxygenation.

VPL Researcher, David Catling (University of Washington), was recently interviewed in a Nature News article discussing NASA’s Perseverance Rover and…

Here we investigate whether magmatic volcanic outgassing on terrestrial planets can produce atmospheric CH4 and CO2 with a thermodynamic model. Our model suggests that volcanoes are unlikely to produce CH4 fluxes comparable to biological fluxes. Improbable cases where volcanoes produce biological amounts of CH4 also produce ample carbon monoxide. We show, using a photochemical model, that high abiotic CH4 abundances produced by volcanoes would be accompanied by high CO abundances, which could be a detectable false-positive diagnostic. Overall, when considering known mechanisms for generating abiotic CH4 on terrestrial planets, we conclude that observations of atmospheric CH4 with CO2 are difficult to explain without the presence of biology when the CH4 abundance implies a surface flux comparable to modern Earth’s biological CH4 flux

Owen Lehmer (University of Washington, Advisor: David Catling) successfully defended his dissertation for his Dual-Title PhD in Earth and Space…

Chemical disequilibrium in exoplanetary atmospheres (detectable with remote spectroscopy) can indicate life. The modern Earth’s atmosphere–ocean system has a much larger chemical disequilibrium than other solar system planets with atmospheres because of oxygenic photosynthesis. However, no analysis exists comparing disequilibrium on lifeless, prebiotic planets to disequilibrium on worlds with primitive chemotrophic biospheres that live off chemicals and not light. Here, we use a photochemical–microbial ecosystem model to calculate the atmosphere–ocean disequilibria of Earth with no life and with a chemotrophic biosphere.

The balance between carbon outgassing and carbon burial controls Earth’s climate on geological timescales. Carbon removal in carbonates consumes both atmospheric carbon and ocean carbonate alkalinity sourced from silicate weathering on the land or seafloor. Reverse weathering (RW) refers to clay-forming reactions that consume alkalinity but not carbon. If the cations (of alkalinity) end up in clay minerals rather than in the carbonates, carbon remains as atmospheric , warming the climate. Higher silicate weathering fluxes and warmer temperatures are then required to balance the carbon cycle. It has been proposed that high dissolved silica concentrations resulting from the absence of ecologically significant biogenic silica precipitation in the Precambrian drove larger RW fluxes than today, affecting the climate. Here, we present the first fully coupled carbon-silica cycle model for post-Hadean Earth history that models climate evolution self-consistently (available as open source code). RW fluxes and biogenic silica deposition fluxes are represented using a sediment diagenesis model that can reproduce modern conditions. We show that a broad range of climate evolutions are possible but most plausible scenarios produce Proterozoic warming (+5 K relative to without RW), which could help explain the sustained warmth of the Proterozoic despite lower insolation. RW in the Archean is potentially more muted due to a lower land fraction and sedimentation rate. Key model uncertainties are the modern reverse weathering flux, the rate coefficient for RW reactions, and the solubility of authigenic clays. Consequently, within the large uncertainties, other self-consistent scenarios where Proterozoic RW was unimportant cannot be excluded. Progress requires better constraints on parameters governing RW reaction rates including explicit consideration of cation-limitations to Precambrian RW, and perhaps new inferences from Si or Li isotopes systems.

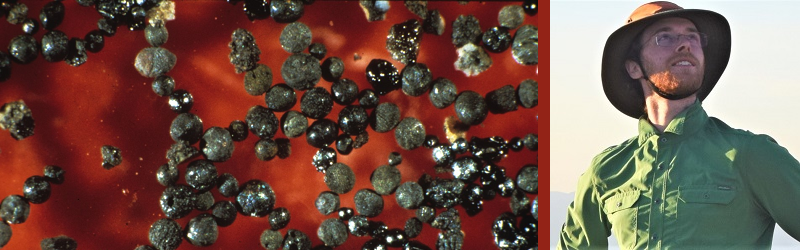

We attempted to use vesicle sizes in lavas erupted near sea-level from the ~2.9 Ga Pongola Supergroup from Mahlangatsha and Mooihoek, eSwatini (formerly Swaziland) and the White Mfolozi River gorge of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa to provide further Archean paleobarometric data. However, reliable results were unobtainable due to small and scarce amygdales, irregular vesicle morphologies and metamorphic mineralogical homogenization preventing the use of X-ray Computed Tomography for accurate vesicle size determination. Researchers attempting paleobarometric analysis using lava vesicle sizes should henceforth avoid these areas of the Pongola Supergroup and instead look at other subaerially emplaced lava flows. With this being only the second time this method has been used on Precambrian rocks, we provide a list of guidelines informed by this study to aid future attempts at vesicular paleobarometry.

The atmosphere of the Archean eon—one-third of Earth’s history—is important for understanding the evolution of our planet and Earth-like exoplanets. New geological proxies combined with models constrain atmospheric composition. They imply surface O2 levels <10−6 times present, N2 levels that were similar to today or possibly a few times lower, and CO2 and CH4 levels ranging ~10 to 2500 and 102 to 104 times modern amounts, respectively. The greenhouse gas concentrations were sufficient to offset a fainter Sun. Climate moderation by the carbon cycle suggests average surface temperatures between 0° and 40°C, consistent with occasional glaciations. Isotopic mass fractionation of atmospheric xenon through the Archean until atmospheric oxygenation is best explained by drag of xenon ions by hydrogen escaping rapidly into space. These data imply that substantial loss of hydrogen oxidized the Earth. Despite these advances, detailed understanding of the coevolving solid Earth, biosphere, and atmosphere remains elusive, however.

University of Washington graduate student and VPL collaborator Owen Lehmer, was the lead author of a new paper recently published…

Earths atmospheric composition during the Archean eon of 4 to 2.5 billion years ago has few constraints. However, the geochemistry of recently discovered iron-rich micrometeorites from 2.7 billionyearold limestones could serve as a proxy for ancient gas concentrations. When micrometeorites entered the atmosphere, they melted and preserved a record of atmospheric interaction. We model the motion, evaporation, and kinetic oxidation by CO2 of micrometeorites entering a CO2-rich atmosphere. We consider a CO2-rich rather than an O2-rich atmosphere, as considered previously, because this better represents likely atmospheric conditions in the anoxic Archean. Our model reproduces the observed oxidation state of micrometeorites at 2.7 Ga for an estimated atmospheric CO2 concentration of >70% by volume. Even if the early atmosphere was thinner than today, the elevated CO2 level indicated by our model result would help resolve how the Late Archean Earth remained warm when the young Sun was ~20% fainter.

VPL co-investigator David Catling (UW) and collaborator Jonathan Toner (UW) recently published a paper in the Proceedings of the National…

Phosphate is central to the origin of life because it is a key component of nucleotides in genetic molecules, phospholipid cell membranes, and energy transfer molecules such as adenosine triphosphate. To incorporate phosphate into biomolecules, prebiotic experiments commonly use molar phosphate concentrations to overcome phosphates poor reactivity with organics in water. However, phosphate is generally limited to micromolar levels in the environment because it precipitates with calcium as low-solubility apatite minerals. This disparity between laboratory conditions and environmental constraints is an enigma known as the phosphate problem. Here we show that carbonate-rich lakes are a marked exception to phosphate-poor natural waters. In principle, modern carbonate-rich lakes could accumulate up to ?0.1 molal phosphate under steady-state conditions of evaporation and stream inflow because calcium is sequestered into carbonate minerals. This prevents the loss of dissolved phosphate to apatite precipitation. Even higher phosphate concentrations (>1 molal) can form during evaporation in the absence of inflows. On the prebiotic Earth, carbonate-rich lakes were likely abundant and phosphate-rich relative to the present day because of the lack of microbial phosphate sinks and enhanced chemical weathering of phosphate minerals under relatively CO2-rich atmospheres. Furthermore, the prevailing CO2 conditions would have buffered phosphate-rich brines to moderate pH (pH 6.5 to 9). The accumulation of phosphate and other prebiotic reagents at concentration and pH levels relevant to experimental prebiotic syntheses of key biomolecules is a compelling reason to consider carbonate-rich lakes as plausible settings for the origin of life.

Constraining the surface environment of the early Earth is essential for understanding the origin and evolution of life. The release of cations from silicate weathering depends on climatic temperature and urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0001, and such cations sequester urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0002 into carbonate minerals in or on the seafloor, providing a stabilizing feedback on climate. Previous studies have suggested that this carbonate?silicate cycle can keep the early Earth’s surface temperature moderate by increasing urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0003 to compensate for the faint young Sun. However, the Hadean Earth experienced a high meteorite impactor flux, which produced ejecta that is easily weathered by carbonic acid. In this study, we estimated the histories of surface temperature and ocean pH during the Hadean and early Archean using a new model that includes the weathering of impact ejecta, empirically justified seafloor weathering, and ocean carbonate chemistry. We find that relatively low urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0004 and surface temperatures are probable during the Hadean, for example, at 4.3 Ga, urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0005 (in bar) is urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0006 urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0007 and temperature is urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0008 urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0009 K. Such a low urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0010 would result in a circumneutral to basic pH of seawater, for example, urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0011 urn:x-wiley:ggge:media:ggge22102:ggge22102-math-0012 at 4.3 Ga. A probably cold and alkaline marine environment is associated with a high impact flux. Hence, if there was an interval of an enhanced impact flux, that is, Late Heavy Bombardment, similar conditions may have existed in the early Archean. Therefore, if the origin of life occurred in the Hadean, life likely emerged in a cold global environment and probably spread into an alkaline ocean.

Using Gaussian process regression to analyze the Martian surface methane Tunable Laser Spectrometer (TLS) data reported by Webster et al. (2018), we find that the TLS data, taken as a whole, do not indicate seasonal variability. Enrichment protocol CH4 data are consistent with either stochastic variation or a spread of periods without seasonal preference.

The partial pressure of atmospheric hydrogen (pH2) on the early Earth is important because it has been proposed that high pH2 warmed the planet or allowed prebiotic chemistry in the early atmosphere. However, such hypotheses lack observational constraints on pH2 . Here, we use the existence of detrital magnetites in (? 3.0 Ga) Archean riverbeds to constrain pH2 . Under the condition of high pH2 , magnetite should disappear via reductive dissolution. We investigated the timescale for a magnetite particle in a river to dissolve, which depends on pH2 and pCO2 . Using published estimates of Archean pCO2 and assuming the presence of Fe(III)-reducing microbes, the survival timescale is ? 1 kyr when pH2 is ?10-2 bar , and decreases as pH2 increases. Considering that the residence time of a particle in a short river (< 1000 km) is ? 1 kyr , the existence of detrital magnetite particles in Archean riverbeds likely indicates that pH2 was below ?10-2 bar . Such a level would preclude H2 as a greenhouse gas or a strongly reducing Archean atmosphere. It is also consistent with limits imposed on H2 by consumption by methanogens because conversion to CH4 is thermodynamically favored.

Cyanide plays a critical role in origin of life hypotheses that have received strong experimental support from cyanide-driven synthesis of amino acids, nucleotides, and lipid precursors. However, relatively high cyanide concentrations are needed. Such cyanide could have been supplied by reaction networks in which hydrogen cyanide in early Earths atmosphere reacted with iron to form ferrocyanide salts, followed by thermal decomposition of ferrocyanide salts to cyanide. Using an aqueous model supported by new experimental data, we show that sodium ferrocyanide salts precipitate in closed-basin, alkaline lakes over a wide range of plausible early Earth conditions. Such lakes were likely common on the early Earth because of chemical weathering of mafic or ultramafic rocks and evaporative concentration. Subsequent thermal decomposition of sedimentary sodium ferrocyanide yields sodium cyanide (NaCN), which dissolves in water to form NaCN-rich solutions. Thus, geochemical considerations newly identify a particular geological setting and NaCN feedstock nucleophile for prebiotic chemistry.

“A group of leading researchers in astronomy, biology and geology have come together under NASA’s Nexus for Exoplanet System Science, or…

(Astrobiology, 2016)

Here, we modeled the amount of H2 O2 that could be produced in an Eoarchean atmosphere using updated solar fluxes and plausible CO2 , O2 , and CH4 mixing ratios. Irrespective of the atmospheric simulations, the upper limit of H2 O2 rainout was calculated to be <10(6) molecules cm(-2) s(-1) . Using conservative Fe(III) sedimentation rates predicted for submarine hydrothermal settings in the Eoarchean, we demonstrate that the flux of H2 O2 was insufficient by several orders of magnitude to account for IF deposition (requiring ~10(11) H2 O2 molecules cm(-2) s(-1) ). This finding further constrains the plausible Fe(II) oxidation mechanisms in Eoarchean seawater, leaving, in our opinion, anoxygenic phototrophic Fe(II)-oxidizing micro-organisms the most likely mechanism responsible for Earth's oldest IF.

Here we use Se isotopic and abundance measurements of marine and non-marine mudrocks to reconstruct the evolution of the biogeochemical Se cycle from ∼3.2 Gyr onwards. The six stable isotopes of Se are predominantly fractionated during redox reactions under suboxic conditions, which makes Se a potentially valuable new tool for identifying intermediate stages from an anoxic to a fully oxygenated world. δ82/78Se shows small fractionations of mostly less than 2‰ throughout Earth’s history and all are mass-dependent within error. In the Archean, especially after 2.7 Gyr, we find an isotopic enrichment in marine (+0.37 ± 0.27‰) relative to non-marine samples (−0.28 ± 0.67‰), paired with increasing Se abundances.

Organic and inorganic carbon isotope records reflect the burial of organic carbon over geological timescales. Permanent burial of organic carbon in the crust or mantle oxidizes the surface environment (atmosphere, ocean and biosphere) by removing reduced carbon. It has been claimed that both organic and inorganic carbon isotope ratios have remained approximately constant throughout Earth’s history, thereby implying that the flux of organic carbon burial relative to the total carbon input has remained fixed and cannot be invoked to explain the rise of atmospheric oxygen (Schidlowski, 1988; Catling and others, 2001; Holland, 2002; Holland, 2009; Kump and others, 2009; Rothman, 2015). However, the opposite conclusion has been drawn from the same carbon isotope record (Des Marais and others, 1992; Bjerrum and Canfield, 2004). To test these opposing claims, we compiled an updated carbon isotope database and applied both parametric and non-parametric statistical models to the data to quantify trends and mean-level changes in fractional organic carbon burial with associated uncertainties and confidence levels.

What fascinates people about astrobiology is that it seeks answers to long-standing unsolved questions: How quickly did life evolve on Earth and why did life persist here? Is there life elsewhere in the Solar System or beyond? Astrobiology: A Very Short Introduction explores some of the big unanswered questions about the universe, considers the origins of life on Earth and its evolution, and brings together the ideas of microbiologists, astronomers, planetary scientists, and geologists. It introduces the origins of astrobiology and demonstrates its impact on current astronomical research and…